By Will Friedwall

June 19, 2006

Say you have a band that already features not one but two bass players. Now, what is the one additional thing that you need the most? If you're Ornette Coleman, the answer is obvious: a third bass player. At Carnegie Hall on Friday night, where - before Mr. Coleman made his first New York appearance in two years - it was impossible not to notice an electric bass waiting on the stage. Still, when the band appeared at 8:05 p.m., it was a surprise that in addition to Greg Cohen and Tony Falanga - the two acoustic players who have been working with Mr. Coleman since 2003 - a third bassist (not in the program or the advertising) was announced: Al MacDowell, who plays the electrified instrument in Mr. Coleman's band Prime Time. Thus the band at Carnegie Hall featured three guys playing the same instrument led by a single man who plays three instruments, since Mr. Coleman, in addition to his iconic white-lacquered alto saxophone, switches to trumpet and violin from time to time.

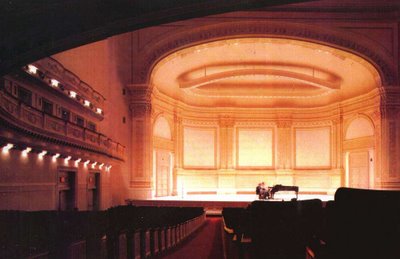

It might make sense to bill this band as "Ornette Coleman's Carnegie All-Stars" since this is essentially the group he has appeared with in all of his recent appearances here, three out of the last four years of The JVC Jazz Festival. With his canny knowledge of everything sonic, Mr. Coleman might well have put this group together to compensate for the bizarre acoustics of Carnegie Hall. The room is the Bermuda Triangle of jazz basses, who too often are reduced to children that you can plainly see but not hear. By and large, the acoustics were not a problem in Friday's concert, except that it was difficult to tell which of the three basses was playing exactly what at certain times. The drummer, Denardo Coleman, Ornette Coleman's son, played very tastefully behind a wall of sound isolating plastic so that his traps could be controlled. He was suitably audible but not overwhelming (rare for drums in any large classical concert hall).

Almost 50 years ago, Ornette Coleman was an innovator who not only gave the world "free jazz" (and later "Harmolodic music") but inspired the atmosphere of experimentation that has been a major part of jazz ever since. Like his best colleagues, contemporaries, and in some cases, progeny, such as Wayne Shorter and Sonny Rollins, Mr. Coleman has consistently adjusted his approach, his musical contexts, his bands, and his own saxophone sound over the course of his career.

Lately, with the Carnegie multi-bass group, his tactic is to organize a composition into short phrases of usually four, six, or eight bars; he plays one phrase, then rests and breathes for a few measures, then elaborates on the previous phrase, rests again, and returns to play a variation on the elaboration, and so on. Mr. Coleman's radical idea, expressed on classic albums like the breakthrough "Shape Of Jazz To Come" in 1959, was that all these variations should be based on the melody line rather than the chord changes, as the beboppers were then doing. In a single step, Mr. Coleman at once made jazz more primitive and more futuristic.

Over the course of a single 80-minute set (consisting of pure music; he doesn't do bandstand humor or even announce song titles), Mr. Coleman played 11 of these mostly-modular compositions. He continually seems to be composing and improvising simultaneously, eliminating the academic difference between the two practices. As in a traditional chord-based solo, he often seems to be getting more and more abstract, that is, further away from the original, stated melody, as he goes along. But he eschews traditional crowd-pleasing stunts like building to a high-note climax or repeating notes or phrases for dramatic effect.

Yet he draws on the history of American music and jazz in surprising ways; often random quotes to various songs appear in his music, and you have to wonder if he's actually alluding to the song that you think he is. For instance, on Friday, he repeatedly played a line from Irving Berlin's "It's A Lovely Day Today" (indeed it was) over the course of the set. In the closing tune of the set, there were fragments from "Beautiful Dreamer," "I Can't Get Started," and especially Harold Arlen's "Blues In The Night," which he lingered on long enough to, in effect, announce to the crowd, "No, your ears are not deceiving you, I'm really playing 'Blues-In-The-Freakin'-Night!'"

More important than references to specific songs, Mr. Coleman was in the mood to allude to different genres: There were long stretches of blues, including one tune that was solidly in the 12-bar (4+4+4) format and even seemed based on blues changes. He also repeatedly slipped into calypso mold, citing the Charlie Parker-associated, "Sly Mongoose," and from there also referenced various Cuban and other Pan-African rhythms (as heard in his own "Una Muy Bonita" of 1959).

The three basses also gave Mr. Coleman the opportunity to reference various kinds of music that he has been part of: Greg Cohen, who mostly played pizzicato (with his hands), embodied the jazz tradition; Tony Falanga, mostly playing arco (with the bow), came from the world of classical and fully-notated music, and Mr. MacDowell, playing electric, represented funk and the blues. The three interacted, both with the two Colemans and with each other, in constantly changing ways, switching rolls of leads and seconds, soloist and accompanist, at times playing several different inter-related melodies contrapuntally. In general, they drew on Mr. Coleman's history with great bassists from Charlie Haden and Scott LaFaro to Jamaldeen Tacuma.

The five men left the stage at around 9:20 p.m., only to return a few minutes later to play one of Mr. Coleman's best-known jazz standards, the 1960 dirge," Lonely Woman. "With typical unpredictability, he felt compelled to announce the only tune that everybody in the nearly sold-out crowd was going to know.